A Rammellzee Exhibition Is Coming to New York

What does it feel like to be mythical? I’d like to ask the ghost of the artist Rammellzee. Even in life, he was described more often as alien than human. He strolled through the streets of downtown Manhattan armored in elaborate costumes that occasionally emitted fire, leaving a trail of rhymes and rumors along the way.

But Rammellzee wasn’t average by any definition. “He just ventured out on this planet in his own dimensions,” his late wife, Carmela Zagari, once said. The art, rap, and cosmologies he conjured not only mesmerized the 1980s art world, within which he came of age, but left a permanent mark on his peers and the artists who came after him, from Jean-Michel Basquiat and Jim Jarmusch to the Beastie Boys, graffiti artist Futura, and cult rapper Wiki. “He’s the kind of guy you could talk to for 20 minutes and your whole life could change, if you could understand him,” Jarmusch once said. Funkmaster Bootsy Collins has described Rammellzee as a “speck of magic galaxy dust from another time.”

Beginning next week, Rammellzee’s mythical life and work will be reincarnated in the artist-polymath’s largest show yet: “RAMMΣLLZΣΣ: Racing for Thunder,” opening at Red Bull Arts New York on May 4th. It will bring together art from all stages of his practice, while confirming his influence on a dizzying spectrum of culture: from painting, assemblage, and performance art to rap, fashion, and philosophy. “It’s not easy presenting a survey of a man, a myth, and an equation as complicated as Rammellzee,” Max Wolf, the chief curator of Red Bull Arts, told Artsy while taking a break from installing the sprawling show. “But it was essential that we try.”

His work first cropped up in the 1970s across New York City’s subway tunnels and cars, where he scrawled intricate graffiti alongside pioneers like Basquiat,

New York in the 1970s was riddled with poverty and discrimination, bolstered by deepening class and racial divides. Starting in the ’50s, poor, primarily black communities had been pushed out of Manhattan all the way to subsidized housing in the beach community of Far Rockaway, where Rammellzee’s family landed. For him, and for many early graffiti writers, spraying trains and walls became a way to let off steam, wield power, and claim space.

Rammellzee’s tags were barbed with sharp, explosive lines that made them look like weapons. This was no accident. He wrote extensively about the alphabet’s ability to wage war against language, misinformation, and a repressive society. “The letter is armed to stop all the phony formations, lies, and tricknowlegies placed upon its structure,” he wrote. “You think war is always shooting and beating everybody, but no, we had the letters fight for us.”

These ideas became the basic components of Gothic Futurism, a philosophy that Rammellzee continued to develop over the course of his life. As time went on, it became a full-blown cosmology, filled with characters hell-bent on saving letters from “being institutionalized, locked into the system that is magnetized to our fridge doors,” as writer Dave Tompkins has noted.

Even his name played a role in this invented world; throughout his adult life, he maintained that Rammellzee wasn’t so much a title as it was a mathematical activation of his theories. When DeAk first met him, he told her: “I’m not an artist, Rammellzee is an equation, and I come in the art scene as a gangster.” In DeAk’s opinion, he was a gangster who “gave more than he took.”

In the ’70s, Rammellzee disseminated Gothic Futurism’s tenets via the subway. “He used graffiti as a viral method to campaign his ideology,” Wolf told Artsy. “The train was like a moving canvas through the city—the blood system of New York.”

But he took his theories beyond the trains, too—even when he gigged as model for Wilhelmina, or during a short stint at the Fashion Institute of Technology (FIT), where he studied jewelry design. Kool Koor, one of Rammellzee’s early collaborators, met him through friends at FIT. “He was already very thorough back then,” he told me. “He had his formulas and theories written down. He seemed like he came through a time portal.”

He also started rapping around this time, and shades of his philosophies emerged in rhyme. He liberated sentence structure by exploding it with absurd poetry, incessant repetition, and the synthesized weirdness of a vocoder. In 1983, he made a track with fellow musician K-Rob called “Beat Bop,” where he introduced himself with a tongue-tying, nasally phrase: “This is the mellow they call the Rammell / That rocks you with the rhythm that’ll shock your spell.” It was produced by their friend, Basquiat, and went onto score Tony Silver and Henry Chalfant’s cult hip-hop documentary, Style Wars, from the same year. Rolling Stone has called it “one of the most revered songs of rap’s early era.”

Whether performing or simply walking around town, Rammellzee’s fingers, waist, and chest were ornamented with thick, studded jewelry; he sported fur-accented hats and coats, and Geordi La Forge-style sunglasses. It was a look that would have been suitable for an intergalactic explorer-hustler—and it would only become more elaborate.

By the 1980s, New York City mayor Ed Koch launched a campaign to remove graffiti from subways. In response, Rammellzee began broadcasting Gothic Futurism through paintings and sculptures forged in his Tribeca apartment instead. They depicted volcanic, cosmic spaces where jagged letters, as sharp as scythes, exploded from shiny pools of resin, leaving splatters of neon spray paint in their wake. Often, they took aim at their enemy—society itself—represented by chains, handcuffs, and gaseous, sickly green clouds.

Curator and writer Carlo McCormick, who co-curated the Red Bull show, met Rammellzee in the early ’80s. By that time, “he had already transformed the act of graffiti into a fine art form and radical philosophy,” McCormick explained to Artsy. “He was always that far ahead of the game, and taking it someplace beyond our understanding.”

Word spread of Rammellzee’s mystical, graffiti-inspired paintings—which were also newly sellable, now that he made them on portable boards instead of on the surfaces of trains. The art world’s downtown galleries took notice, and he began showing across the U.S. and Europe.

In 1987, he had a sprawling exhibition of paintings (and 800-pound spray-painted marble sculptures) at Galleria Lidia Carrieri in Italy. By that point, he had already gone from illegal street artist to critical darling. That same year, in an Artforum review of a New York solo show, McCormick noted that Rammellzee had already “propelled…to stardom.”

A diverse swathe of works from this era will fill Red Bull’s second floor. But the real Gothic Futurist gold is on the first floor, where the sculptures and theories Rammellzee developed in the 1990s and 2000s will be brought to life in an all-encompassing installation depicting his cosmic, semiotic war. “The viewer will walk through a battle that’s poised to kick off,” Wolf explained.

Around 1991, Rammellzee began exhibiting less and retreating into his home-cum-studio more. “The shows started to thin, but the myth was only gaining steam,” said Wolf. “His theories became more complex and it marked the beginning of what, arguably, was his magnum opus.”

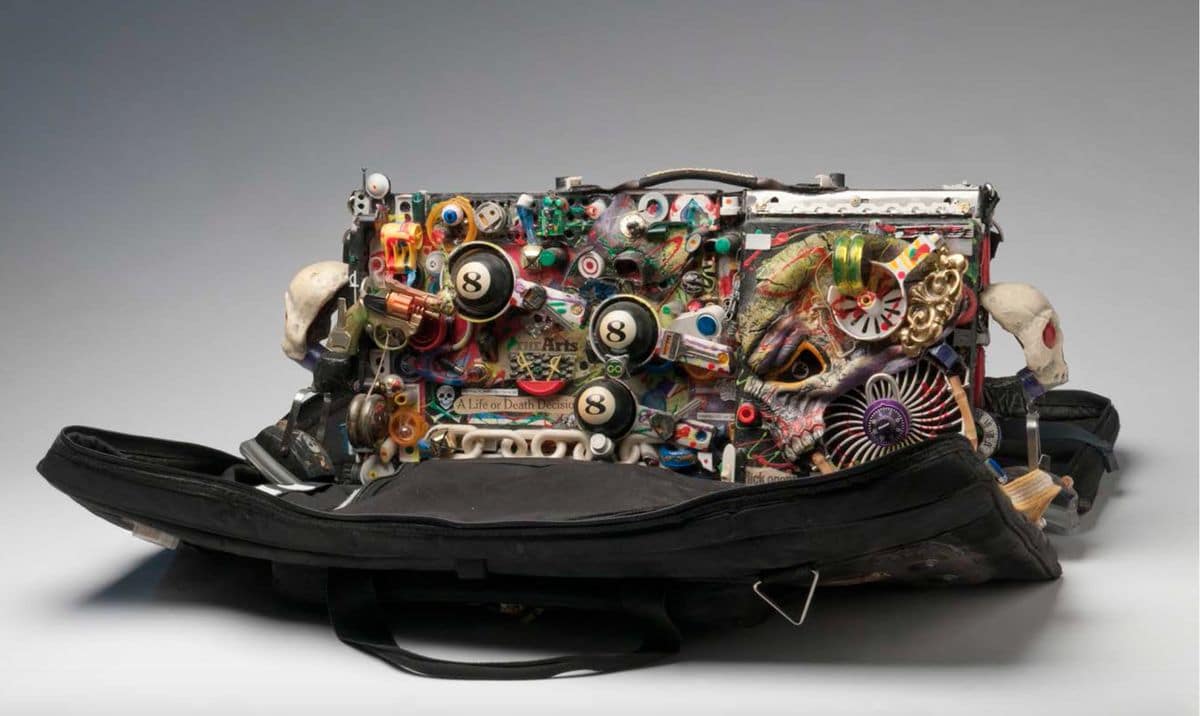

Rammellzee would occasionally descend onto Canal Street to forage for materials, like skateboards, doll heads, and Crown Royale caps. But it was inside his apartment where he was most comfortable. While some have referred to Rammellzee’s retreat into his “Battle Station” as a hermetic move, McCormick told Artsy that his “turn away from the commodity market of paintings…to a deeply internalized space of creating a cosmos in his studio” was “epic and visionary.”

There, he began to fashion scavenged materials into a three-dimensional army of liberated letters, which he called “Letter Racers,” as well as the characters and magical objects that existed in their Gothic Futurist world. He rarely left the Battle Station as Rammellzee, instead choosing to emerge as one of his 22 cosmic characters, called “Garbage Gods,” like Alpha Positive, Crux the Monk, or Igniter the Master Alphabiter.

Occasionally, when he was feeling social, he’d invite friends over. Rumor has it that he was more open to visitors who came bearing Olde English 40-ounces, his beverage of choice. Filmmaker Charlie Ahearn, who included Rammellzee in his seminal graffiti documentary, Wild Style (1983), was a regular at the Battle Station in the ’90s. In a recent conversation with Artsy, he remembered it as a “densely organized mass of Letter Racers, Garbage Gods, Paintings, masks and piles of manuscripts.”

Painter Delta 2 was there, too. He helped Rammellzee in the studio, and often performed as one of Rammellzee’s characters: Delta. He remembers the Battle Station vividly, as a bursting repository for the artist’s never-ending stream of ideas and the work that resulted. When I spoke with him on the phone recently, Delta remembered asking Rammellzee where they’d store all of his swiftly accumulating artwork. “Put it the toilet, put it in the closet, put it in the sink. We’re gonna keep rocking,” he responded. “We have to build this so they remember that we lived.”

While he’s no longer here to witness it, Rammellzee’s legacy lives on in the vast cache of work he left behind. The artist died in 2010 at the age of 49, due to complications resulting from years of alcohol consumption and the inhalation of toxic fumes produced by the resin he used to make his work.

Delta’s a tough guy, who’s written graffiti in some of New York’s roughest neighborhoods and served time in prison, but when we talk about Rammellzee, he gets emotional. “I never thought he would die,” Delta said. “I thought he would last forever and ever. Maybe find a new heart, or make it.”

Indeed, when talking about Rammellzee—mythical figure that he is—the prospect of immortality or reincarnation doesn’t seem implausible.

“I could see him making believe he’s dead and coming back in 10 years,” Delta continued, with a chuckle. “He’s probably laughing right now saying, ‘C’mon. Let’s rock and roll.’ I hope that’s what happens. We’ll see how things go.”

Alexxa Gotthardt is a Staff Writer at Artsy.

Source de l’article: Artsy