Rammellzee, From Living Letters to Living Sculpture

The universe of the graffiti master turned astrofunk storyteller in a bracing show reveals his lifelong battle against the limitations of form.

The graffiti writer, rapper, sculptor, quasi-outsider artist and unorthodox philosopher of language known as Rammellzee was given to enigmatic dissertations, and near the front of the bracing survey of his work, “Rammellzee: Racing for Thunder,” there is a media station with a telling page from one of them.

On it, he sketches the evolution of graffiti’s engagement with individual letters. Up top is Bomberism, which in his rendering is soft, almost cuddly. Beneath that is Wild Stylism, in which the letter is denatured and recast as a futurist puzzle. For many, that was graffiti’s great formal shift, the thing that elevated tagging to speculative art.

But at the bottom of that page is Rammellzee’s own invention — Ikonoklast Panzerism, in which the letter had been distended further, shaded and reconstructed into something gleaming and weapon-like. What started as a simple E became a narrative character — prepared for a fight, ready to peel off the page and start shooting.

Ever since he was a teenager in Far Rockaway, Queens, a precocious kid with an artistic bent and a propensity for tinkering, Rammellzee wanted to make letters into weapons. He saw language as a system of domination, and understood that whoever controlled the letters controlled much more than that.

From Rammellzee’s Garbage Gods series, “Vain,” 1994-2001. The outfits are part Kabuki, part horror film, part techno-dystopic craft fair.

And so for much of his career, from making graffiti in the 1970s to building vivid character figures in the 1990s, sending letters off to war was his animating force.

“Rammellzee: Racing for Thunder,” at Red Bull Arts New York through Aug. 26, includes more than 150 of his pieces spanning four decades. It is the first survey of his work on this scale, through his graffiti and gallery days and concluding with his outsider art of the 1990s and beyond. Where he once sought to give letters a life of their own, by his death in 2010, he had more or less become his art, thanks to a self-contained universe of wearable and inhabitable work that intruded onto, shaped and recontextualized his day-to-day life.

From Rammellzee’s Garbage Gods series, “Vocal Well’s God (chimer),” 1994.

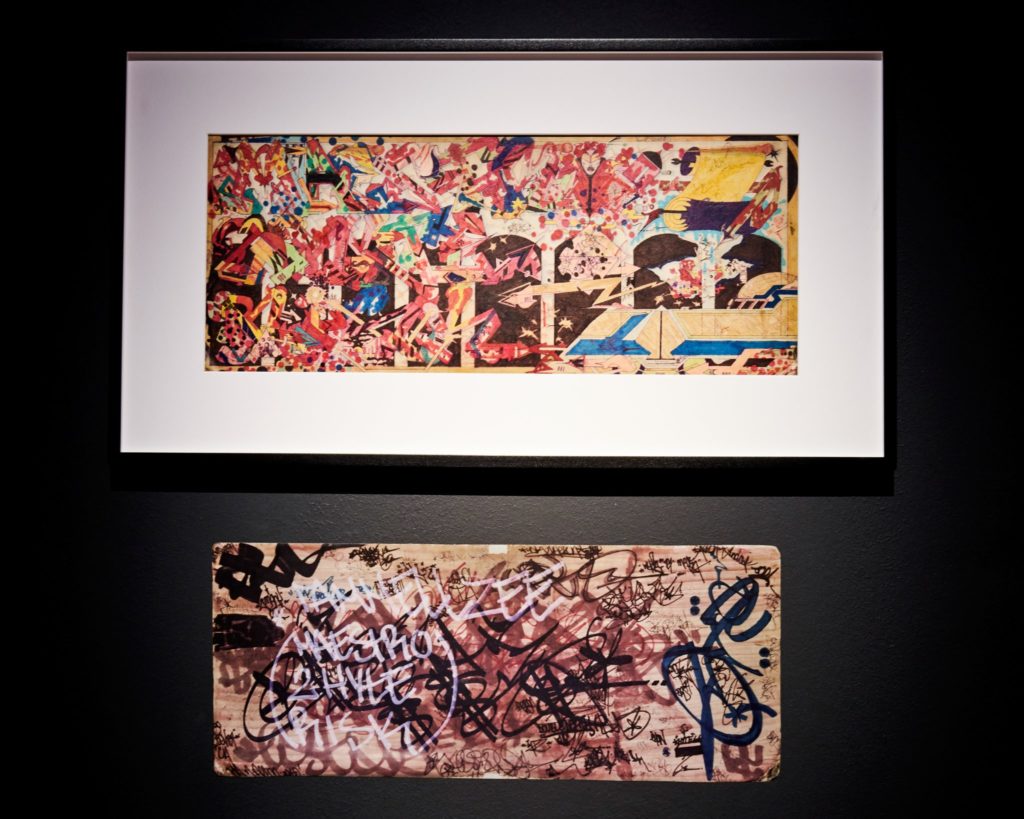

Graffiti was never intended to be archivable, so there are only a handful of examples of Rammellzee’s earliest work here. They are largely startling, though. “Maestro 2 Hyte Risk” (1976-79) is a robust riot of animate letters, and “Evolution of the World” (1979) turns graffiti grammar into longitudinal astro-funk storytelling.

What’s clear throughout this phase is his emerging battle against the limitations of form. Like much of hip-hop in its protean era, Rammellzee conceptualized his work in terms of resistance — against the world at large, but also, in his case, against the frameworks that were fast beginning to congeal on the trains as well as in the galleries newly flirting with street art. Jean-Michel Basquiat was a contemporary, a friend, a competitor and an occasional antagonist of Rammellzee’s. Basquiat produced Rammellzee’s best known song, “Beat Bop,” and immortalized him in the painting “Hollywood Africans” (1983).

Miniature figures of Garbage Gods from the Rammellzee show at Red Bull Arts New York.

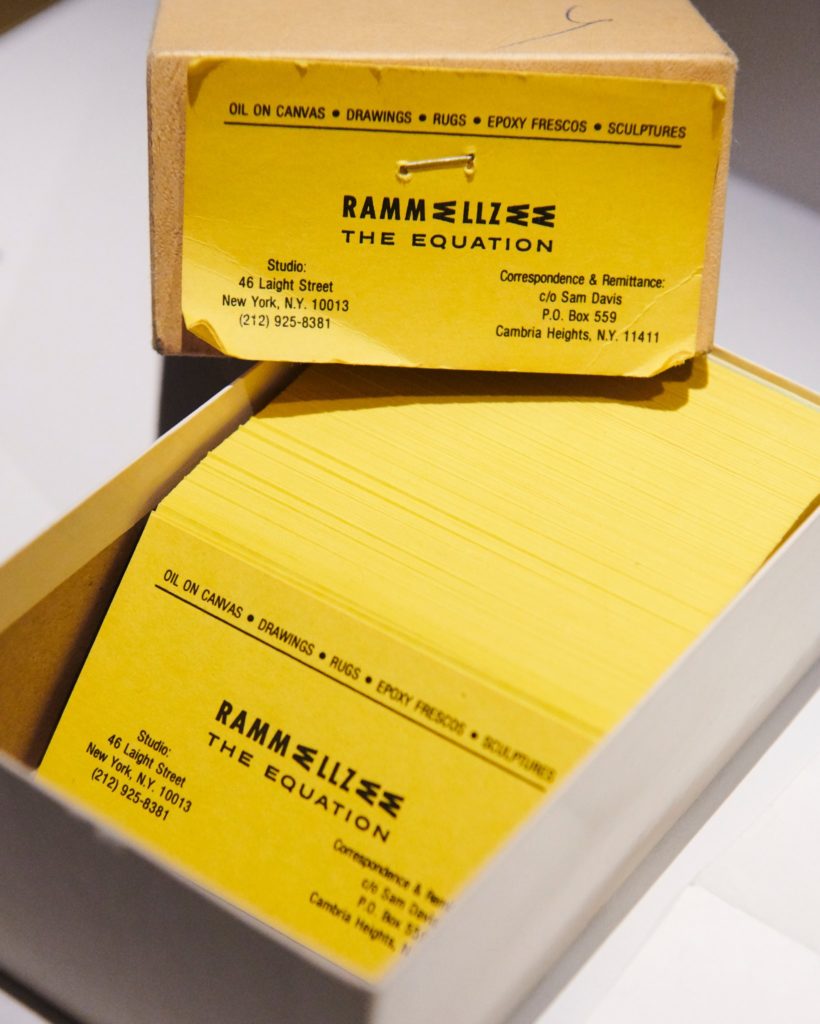

Rammellzee — the child of an African-American mother and Italian father, and a model in his teenage years — also pushed back against his corporeal self, in what would become a recurring theme. He legally changed his name to Rammellzee, and he frequently referred to himself as an “equation.” (“Ramm’s name was a construction site,” the artist Lee Quinones says in one of the exhibition’s audio packages.) There is even, among the ephemera included in this exhibition, a business card advertising the services of Rammellzee, the Equation.

By the beginning of the mid-1980s, Rammellzee was becoming a favorite of progressive European gallerists, and his work was moving onto more formal canvases. But these pieces, when he was transitioning from fantastical 2-D representations into three dimensions, and nodding weakly in the direction of abstraction, are the least purposeful and challenging here — showing an artist constrained, not liberated, by success.

“Maestro 2 Hyte Risk” (1976-1979), pen and marker on cardboard, is a robust riot of animate letters.

In his graffiti, Rammellzee was precise and imaginative — a virtuoso of detail. (In one of the audio stations, his brother recalled him putting together car models as a child and then cutting them apart with an X-Acto knife.) By the late 1980s, he’d returned to that approach, but in mixed-media work. In resin and epoxy, Rammellzee found freedom. It made unusual juxtapositions and unconventional shapes possible. It allowed him to repurpose the detritus he found on the streets into beauty, a stroke of resistance all its own.

And most crucially, it brought the letters to life. Two of his inventive, fascinating Letter Racer sets, from 1988 to 1991, are included here — small wheeled sculptures composed of found items collaged into forceful warrior shapes and arranged in the gallery in triangular battle formations. (There is also a brief video showing off each letter’s corresponding Racer in detail.) Finally, he’d liberated the letters from the train wall and made them the superheroes he’d always proposed that they were.

Some of the 19 Garbage Gods by Rammellzee at his survey at Red Bull Arts New York.

Considering that these micro battlebots are made of industrial effluvia, they are remarkably coherent and pointed. They also reflect the vision of an artist not content to make art for the purpose of observation or transaction, but rather used it as a tool to bring philosophy to life. And he was moving toward creating a full-scale lived-in environment that ignored art as object and replaced it with art as oxygen.

Every part of Rammellzee’s life was oriented this way. This show — curated by Max Wolf with the critic Carlo McCormick — includes a set of his watches, encrusted beyond conventional functionality. It spotlights manifestoes he wrote that laid out the arguments for his worldview, and includes videos of him in galleries lecturing people about his philosophy, looking to spread his ideas.

Rammellzee’s business cards on display at his show at Red Bull Arts New York.

And over time, he built himself into his art. His Laight Street apartment was called the Battle Station, and almost everyone who describes visiting him there noted, with retroactive concern, the intensity of the chemical smell. He lived among his resins and the creations they made possible — his art had become his life. (Rammellzee died at the age of 49 of heart disease.)

Unlike the main floor of the show, which is well lit, the basement is dark (thanks in part to black light) and is filled with the fantastical creations of these later years. Right away, you are met by the Gasholeer (The RAMM: ELL: ZEE), from 1987 to 1998, an epic, spare-parts statue with a keyboard gun, serving here as a kind of sentry guarding the ecosystem Rammellzee built for himself.

But by this stage of his life, Rammellzee wasn’t interacting much with the traditional art world. He stayed mostly in the Battle Station until he was forced out in the early 2000s. The work he made was for himself to inhabit, a personal mythology given physical form.

On the one hand, the Garbage Gods were costumes, yes — he sometimes wore them in public — but they were also the logical continuation of his earliest experiments with graffiti. He started out trying to bring his drawings and sculptures to life. But by the end, he himself had become the sculpture.

Rammellzee: Racing for Thunder

Through Aug. 26 at Red Bull Arts New York, 220 West 18th Street, Manhattan; 212-379-9417, redbullarts.com.

Source: The New York Times