The Art of Disruption

A new exhibit honoring the genius of Rammellzee — a cult hero who made waves in street and fine art, music, film and New York’s cultural landscape — shows how a rule breaker can change the game.

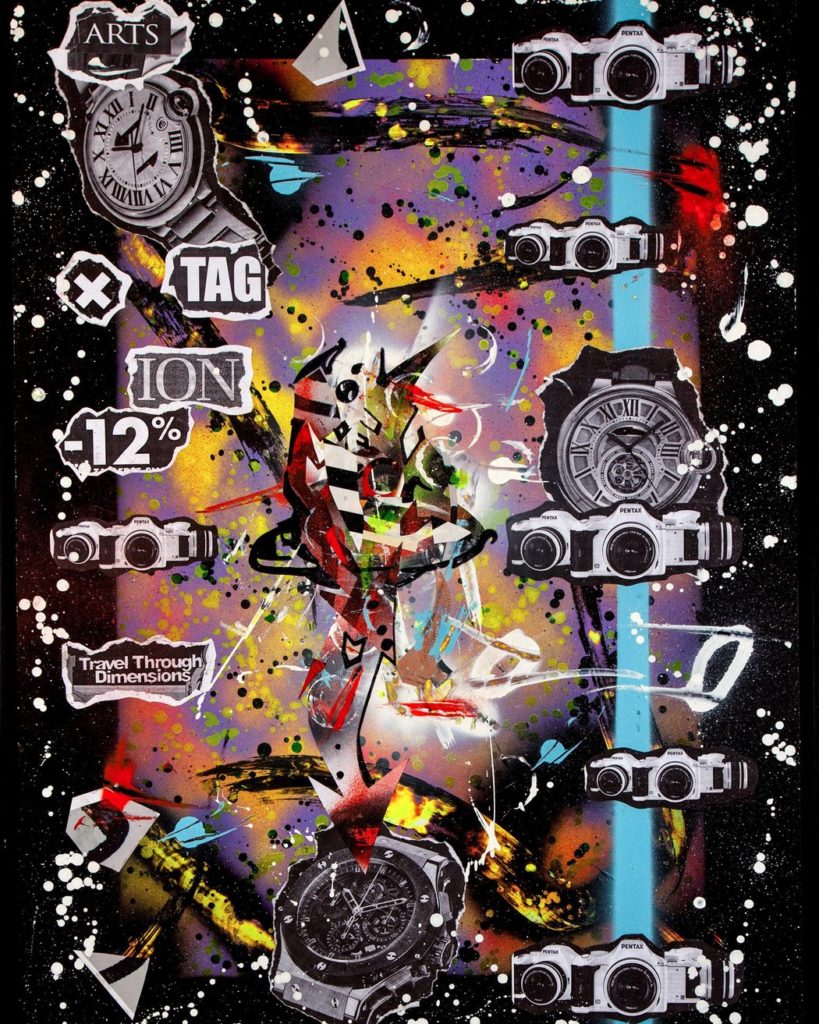

“Atomic Note Tag Minus 12%”

Open any English dictionary and it’s right there in the front: the straight dope on a centuries-old battle for the truth. Not finding it? Well, then, “read it backwards,” Rammellzee, the hip-hop pioneer and visual artist, insists. Then, perhaps, you’ll see what he’s getting at: The Indo-Germanic language tree is a technology of war. The medieval monks knew this, as did the 1970s graffiti writers of New York. The letters of the Western alphabet are soldiers. Each can be destroyed, but also armed to defend itself.

Seated at a desk, headphones on, behind a mic, Rammellzee is dropping this knowledge during a radio interview, circa 1999. He’s 38 at the time, wears a black polyester do-rag, has alert, if tired, eyes and flashes an easy, knowing smile. Beneath it, though, one senses the frustration of the outsider artist. Like many who had questioned the artist before, the radio host is a bit baffled, and, really, who can blame her. The alphabet is at war? Is he for real?

Rammellzee first set down his theory of typographical conflict in a manifesto as a teenage graffiti writer in 1979. He described the arrows in letters sprayed on subway trains as defenses against exploitation, and the cars carrying these letters as tanks in battle. He called his treatise “Ikonoklast Panzerism.” And while he would manage to make his living as an artist soon after, the struggle to subvert and liberate language remained literal for him. His craft. He had a name for this, too: Gothic Futurism.

“I’m an arms dealer,” he tells his radio host. She thinks he means this figuratively, that by “arms” he must mean the rhetoric he raps as an MC. “No,” he insists. “I make real weapons and I sell them … I’ll make you one. »

« Rammellzee is just that sort of genius/madman »

Though he never gained the renown of his onetime collaborator, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Rammellzee was something of a muse to the more celebrated painter and sold plenty of paintings of his own after making the leap from subway cars to downtown galleries. Graffiti writer, recording artist, verbal prankster — Rammellzee was all of these, but he deployed many “weapons,” including paint, epoxy, plaster, plastic, marble and other people’s trash — which he reassembled and fashioned into elaborate costumes, masks and toys, each with a role to play in sagas he could recite long into the night.

“The hysterical intensity of New York’s manic pace produces in its fission/fusion of diverse cultures and social positions a mutant by-product of rational insanity that periodically manifests itself as some new cult hero,” culture critic Carlo McCormick wrote in an « Artforum » review of one of his shows. “Rammellzee is just that sort of genius/madman.”

He quickly branched out in his 20s. In 1982, he took the stage for the climactic scene of Charlie Ahearn’s groundbreaking hip-hop film, « Wild Style ». (His nasal “Gangsta Duck” delivery would later be cited as an influence on Cypress Hill and the Beastie Boys.) A year later, Basquiat produced a test pressing, “Beat Bop,” featuring Rammellzee in a duet with rapper K-Rob. It became a collectible touchstone and a theme for Henry Chalfant’s « Style Wars, » a documentary on graffiti artists that critic Greg Tate called “the most revelatory film about hip-hop ever made.” Rammellzee, in character, also made a memorable cameo in Jim Jarmusch’s 1984 cult classic, « Stranger than Paradise. » His own residence/studio in New York, which he dubbed the Battle Station, became a pilgrimage site for select musicians, graffiti artists and eccentrics. “Rammellzee is a special piece of magic galaxy dust. The Magic Scriptulator,” bass player Bootsy Collins reportedly said when he and George Clinton, the leader of the P-Funk collective, visited in 1987.

There wasn’t, and won’t be, another one like him.

Joe La Placa

Is Rammellzee best understood as a performance artist who dabbled in the visual arts, a serious artist who also rhymed, a scene maker? These are questions, the « New York Times » Randy Kennedy observed, that Rammellzee himself made it difficult to answer with certainty. A new survey of his work opening May 4 at Red Bull Arts New York, « Rammellzee: Racing for Thunder, » will give audiences a chance to make up their own minds. The show, which integrates everything from his early 1980s post-graffiti work to the “Garbage Gods” that populated the Battle Station, also reveals how busy Rammellzee kept during his 49 years, before passing away in 2010.

“There wasn’t, and won’t be, another like him,” say Joe La Placa, the co-founder of the Gallozzi-La Placa Gallery and a dealer who sold Rammellzee’s work for years. “I remember the first time we met, we were talking about letter forms, which I came to from an art-historical perspective, from my interest in the Italian futurists, while he came to it from the [graffiti] writers. We talked about how literacy was power in the Middle Ages, and he told me a story about the monks hiding a letter from God in hell … Then he said that letters didn’t just carry symbolic meaning but contained energy that can be released, like a split atom. And that blew my head off. »

The Battle Station

At 6’3″, Rammellzee was a tall drink of Olde English, and slender in his youth, so that the overcoats he favored hung loose and made him lankier looking. He often wore ski caps and goggles, or three sets of shades in a stack on his forehead, including those wraparounds with the narrow slit that look like they’re for viewing nuclear tests.

What author Jennifer Clement remembers first about him was his gait. “He walks or rather glides in big steps leaning backward with a bop in his walk,” she writes in « Widow Basquiat, » her intimate portrait of Suzanne Mallouk and Mallouk’s love affair with Basquait. Rammellzee, Clement writes, loves slang, “calls girls ‘freaks’ and boys ‘crimees,’ for criminals.” When he sleeps at Suzanne and Jean-Michel’s loft, “he never takes off his shoes or hat. He says he does this in case he needs to make a quick getaway.”

Born in late 1960, Rammellzee grew up in Far Rockaway, Queens, in the Carlton Manor Projects, block towers on the beach. Raised by a police officer, he was, by 14, one of the very punks his father figure was meant to catch. He and his crew created markers from empty cigarette lighters, filling them with purple supermarket ink and stuffing shredded erasers in the top for an applicator. “It would leak all over your pockets, but you could hit a train,” Rammellzee told Greg Tate. “’Course, when you got home you got your [ass] beat because your pants were all fucked up.”

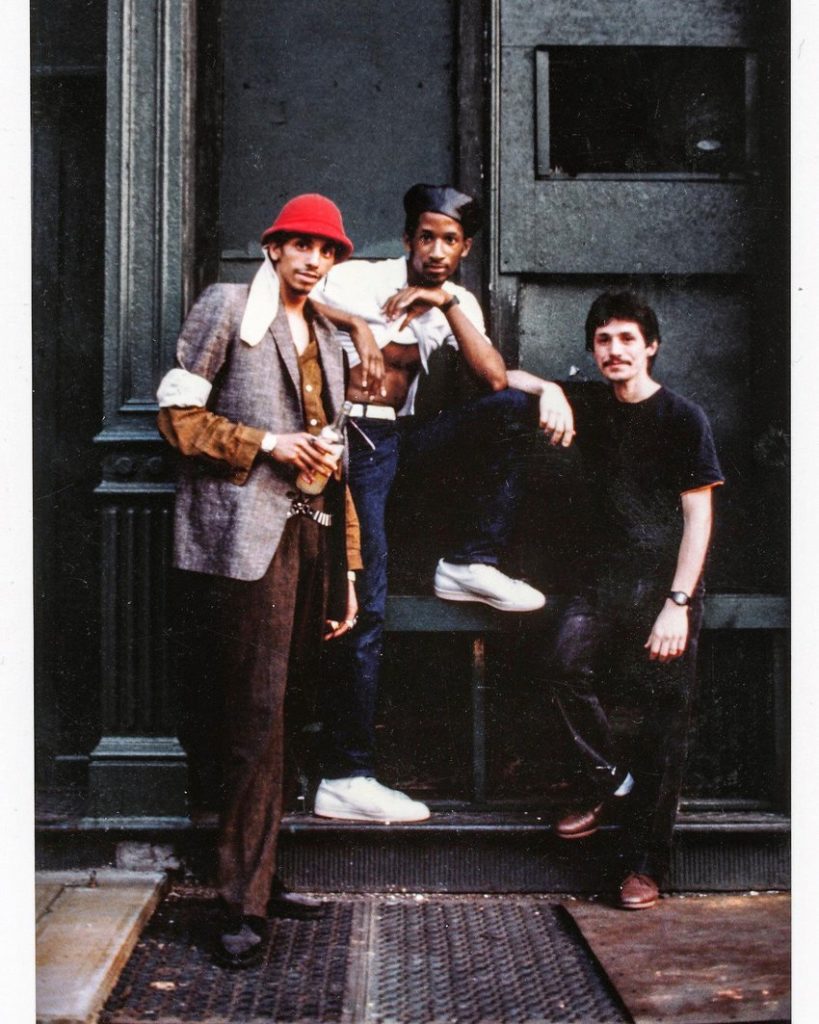

Rammellzee and his peers

Once he reached working age, Rammellzee held the usual array of random jobs that seem, in retrospect, crucial to an artist’s development. He signed with a modeling agency. He attended classes at the Clara Barton School for Health Professionals in Brooklyn, where he worked on mouth guards and dentures — the kind of precise handiwork that he’d later employ for his assemblage projects. He reportedly worked as a diver for his uncle on an oil rig, where, music historian Dave Tompkins writes, he “learned to punish his diaphragm like a monk” — preparing him for generating interesting sounds on the vocoder, the electronic voice-altering device Tompkins traces from Bell Labs to hip-hop in his excellent 2010 book « How to Wreck a Nice Beach. »

While diving, Tompkins notes, Rammellzee “ingested his fair share” of less dense air, gas mixtures that allowed him to cartoon his vocal pitch. “Yet he learned the Gangster Duck style not from frogman helium but Jahmel, a rapper he’d met at a Far Rockaway Police Athletic League center, where they would change voices and get-ups to trick the cops.” “I owe my life on the mic to that dude,” Rammellzee told Tompkins.

Committed to improving as a graffiti writer, Rammellzee made a successful effort to meet the muralist Dondi, who became something of a mentor to him. Later, when an alleged graffiti artist, Jean-Michel Basquiat, began making a name for himself downtown, Rammellzee took it upon himself to interrogate him. No one had seen his graffiti tag, because Basquiat had never written on a train.

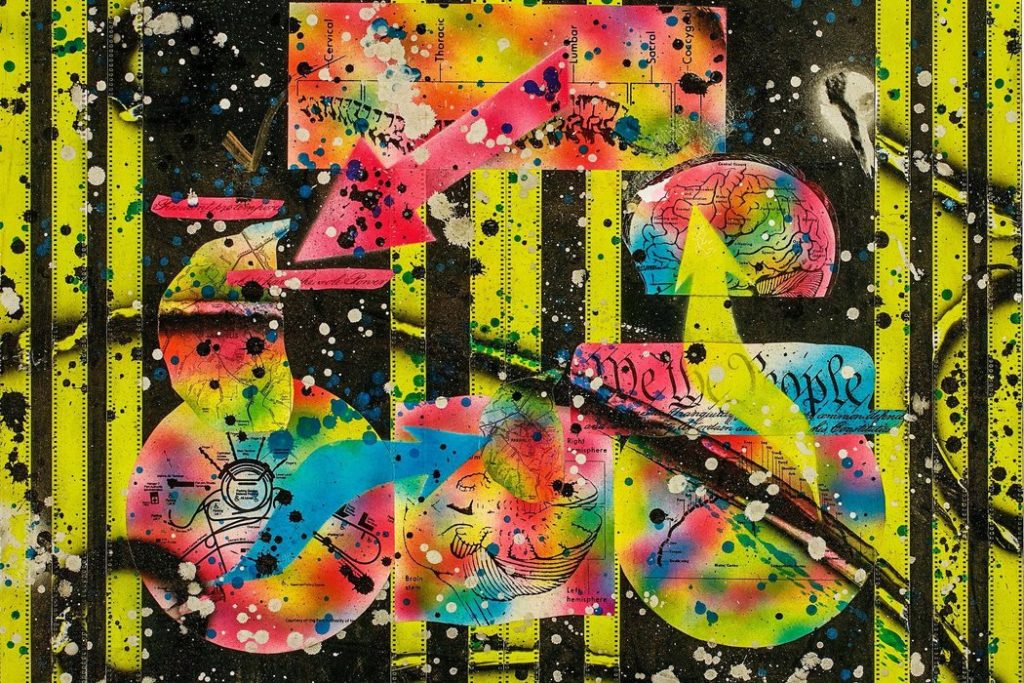

Knotted Minds, » 1998

Though their meeting was contentious, the two became friends. Basquiat later took Rammellzee to Los Angeles, where they stayed in the same Chateau Marmont bungalow in which John Belushi had died. That trip is immortalized in a snap by photographer Stephen Torton of the two of them outside Disneyland, as well as in “Hollywood Africans,” Basquiat’s 1983 painting that includes a sketch of Rammellzee (which hangs in the Whitney Museum of Art).

“Like everyone, Rammellzee had a falling-out with Jean,” Mallouk told Clement. “I got the impression that he thought that Jean had sold out to the white art world. But I know that deep down he always loved Jean.”

Though he was never estranged from his own family, Rammellzee said they didn’t know what to make of him. “Nobody in my family likes what I do,” he told Tompkins. “They damn sure don’t understand how I got to New York and how I got to stay.”

His early paintings and work in resin reportedly sold well. “Hell the Finance Field Wars,” which Wild Style director Charlie Ahearn considers one of his finest paintings, hung in the Tokyo Supreme store on its opening night. Often overlooked, too, is the time he spent living and working on marble sculptures in Martina Franca, Italy. In 1988, Rome’s Galleria Lidia Carrieri published a book of his work. That same year, he and the bandmates Shock Dell and Delta II collaborated on Gettovetts: « Missionaries Moving, » an album for Island Records, but it tanked.

When he returned to the Battle Station, Rammellzee began to work in earnest on his bricolage, work that culture critic Mark Dery later seized on as an example of “Afro-futurism” in the 1994 essay that introduced that term. A hot topic today in the wake of « Black Panther’s » monster success, Afro-futurism, Dery suggests, includes speculative fiction and other art that addresses African-American concerns in the context of technoculture. As examples, Dery lists John Sayles’ « The Brother from another Planet » (1984), « George Clinton’s Computer Games » (1982) and “the intergalactic big-band jazz churned out by Sun Ra’s Omniverse Arkestra.” Dery also found it in the Gasholeer, a suit of Samurai-like armor Rammellzee spent four years building from materials plucked from New Yorkers’ trash, “a 148-pound, gadgetry-encrusted exoskeleton,” in Dery’s phrase, that not only shoots flames from its heels and throat, but with its “dangling, fetish-like doll heads and its Computator cobbled together from screws and wires, speaks to dreams of coherence in a fractured world, and to the alchemy of poverty that transmutes sneakers into high style, turntables into musical instruments, and spray-painted tableaux on subway cars into hit-and-run art.”

“Much of what Rammellzee did qualifies as Afro- futurism,” says Reynaldo Anderson, the Humanities chair at Harris-Stowe State University and co-editor of « Afrofuturism 2.0: The Rise of Astro-Blackness. » “He is right at the intersection of the black experience and these European forms. These Gothic letters he wants to wrest out of medieval societies.” Anderson notes that Rammellzee incorporates insights, codes, wordplay and “trick-knowledge” consistent with black American figurative traditions and inner-city groups, such as the Five Percent Nation, a splinter from the Nation of Islam.

Given the groups and scenes he moved between, it’s tempting to view Rammellzee as a Zelig-like figure — the Forrest Gump of the hip-hop and art worlds, as the « Village Voice » once put it. Music historian Jeff Mao cautions against this. Mao collected oral histories from Rammellzee’s friends and collaborators for the new Red Bull exhibition.

“He was an intensely charismatic individual presence who made an indelible impression on everyone who encountered him,” Mao says. “But he was too singular and uncompromising to be defined or confined by any scene. Ultimately, a force of nature like that separates itself from the crowd.

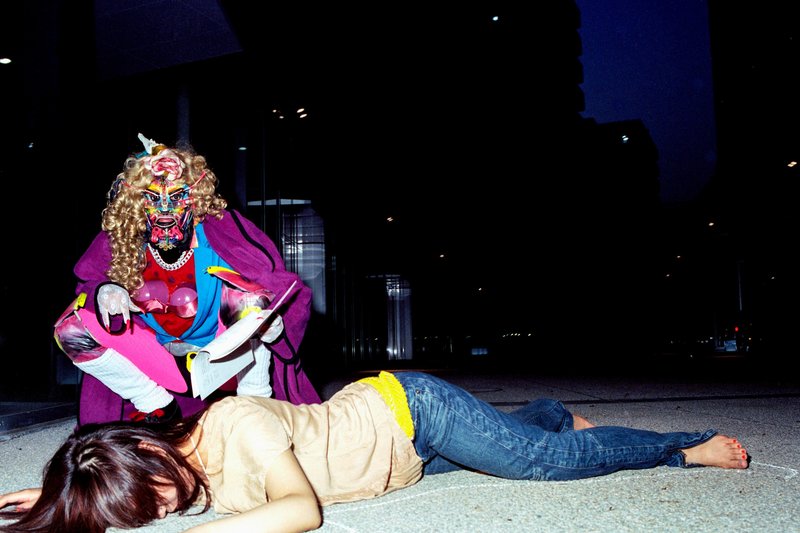

Vain the Insane

Though he was intensely productive, Rammellzee’s Tribeca residence, the Battle Station, might well have been his magnum opus. He filled this loft, on the fourth story of a building on Laight Street, with his creations. It got to the point where he could pull on one of his ersatz costumes and all but disappear, camouflaged in his own cabinet of wonders, eyes blinking out from a world assembled from dumpster trash. “He crammed it all in, but it wasn’t just chaos,” Ahearn says. “He was meticulous.”

Visitors to the Battle Station never knew what might unfold. Pilgrims might be given a lengthy tour, with Rammellzee sharing the particular origins, traits and destinies of each of his characters. The first time he entered, Tompkins recalls in « How to Wreck a Nice Beach, » Rammellzee introduced him to the Mettroposttersizer, an “electromagnetic planet-smasher that causes ‘The Wizard’s Game of Pool,’ leaving the solar system in a ‘molten state.’ Also referred to as ‘another reason to drink beer.’ ” On a subsequent visit, Tompkins found himself parked on minivan backseat, looking up at “a fleet of skateboards and souped-up Tonka chassis … Each is an armored letter from Rammel’s transuniversal alphabet, aeronautic structures of disfigured angles and points, encrypted and long estranged from the word itself, now helmed by plastic dragons, doll heads and dimetrodons, sprayed in gold.”

Each of his costume characters had a part to play in his Gothic Futurism universe, Rammellzee explained to Tate when he crossed the threshold: “Some of them are from different time periods. The Purple People Eater over there is China, the Cosmic Bookie … He places his bets with the Horrors, and the Horrors Gamble galaxies. The Wielder is dealing with Chronologics. He spins around and deals with Ovulization. He has to deal with the bet called ‘Womb versus Man.’ ” Tate would later write that, listening to Rammellzee, it’s hard to know what’s cosmology and what’s a child’s make-believe, but “you be the judge. Ramm don’t care, ’cause Ramm don’t stop.”

A Rammellzee costumed character

Shortly after the September 11 attacks, the owner sold the building where Rammellzee and Zagari resided. It was, Dave Tompkins later wrote, the only time he saw Rammellzee somber: It meant he had to move the Battle Station.

The couple relocated nearby, to Battery Park City, to a more conventional apartment, forcing much of the Battle Station into storage. Money, too, became more of an issue: Rammellzee hadn’t had to pay rent on the Battle Station for years. It had been a squat.

The cause of his 2010 death, like his birth name, is not certain.

Rammellzee kept working — performing with guitarist Buckethead at the Knitting Factory, for instance, and providing work for a solo exhibition in Zurich. But in his final years, friends saw less of him and could tell he wasn’t well. According to the « New York Times, » heart disease was the reported cause of his 2010 death, but La Placa and other friends suspect the epoxies he used (working without a respirator) and drinking had taken their toll on him, too. He’d been in noticeable decline since he had a seizure in 2008. (Zagari died in 2012.)

While Rammellzee was still alive, curator Jeffrey Deitch approached him about mounting a new show in New York, but he became fixated on an impractical idea: to fill the entire volume of Deitch’s gallery with resin. After his death, gallerist Suzanne Geiss assisted Deitch in re-creating part of the Battle Station for « Art in the Streets, » a survey exhibition at MOCA in Los Angeles in 2011. Geiss also negotiated with his estate to assess what Rammellzee had in storage.

“I can’t imagine what others might have thought opening the storage unit — like, what is this pile of junk?” Geiss recalls. “He’d had a deep fryer at the Battle Station, so everything was coated in this residue of grease. We moved it all to a warehouse and spent seven months cleaning and cataloging it. It was like an archaeological excavation.” From this wreckage, Geiss rescued nearly three sets of Rammellzee’s “Letter Racers” — the TIE-Fighter alphabet — that Tompkins once sat beneath, and built an inaugural show for her own gallery. Several of these pieces are included in the New York show.

« Gulf War » 1991

Also in the show is Rammellzee’s legendary Gasholeer. “As a costume and a sculptural object, it’s an assemblage masterpiece,” says Max Wolf, the show’s chief curator. “And as a walking synthesizer, and fully functioning, fire breathing, exoskeleton, it’s Ramm’s greatest self-portrait.”

All along, Rammellzee obsessed over letters and letter forms, and his theories about his work — some of it clever, some of it incoherent — challenge you to question any information you trust. Even the name he took is not a name, he said, but an equation, and is properly written with sigmas, not epsilons (RAMM∑LLZ∑∑). Who is to say, finally, if it is, or isn’t?

Though his theories and name added to his intrigue, they contributed to his obscurity, too, but that will likely change, Wolf says, as today’s crop of young, multidisciplinary artists discover his freakish talent. On the mic or on canvas, and in his own person, he was a provocateur; his greatest work of art, arguably, was his own myth.

“He was the art,” Ahearn agrees.

« Rammellzee: Racing for Thunder » runs May 4 through Aug. 26 at Red Bull Arts New York.

Source: Red Bull